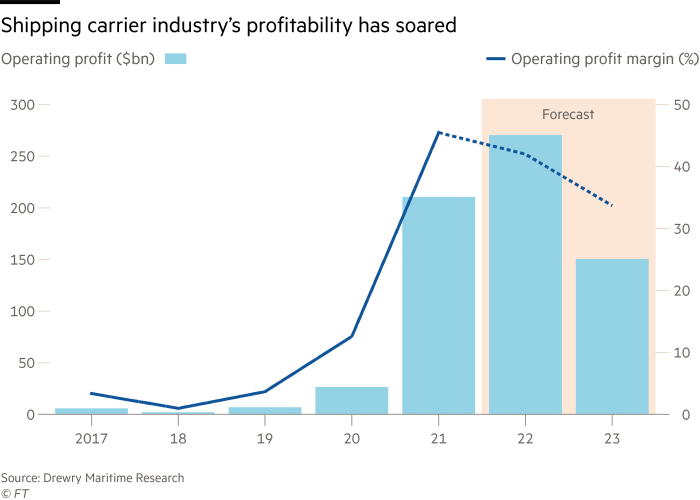

In just three years, the container shipping industry will have made as much money as the entire previous six decades.

Propelled by soaring demand following the pandemic, shipping groups have enjoyed a level of profitability that few in the notoriously volatile sector could have dreamt of.

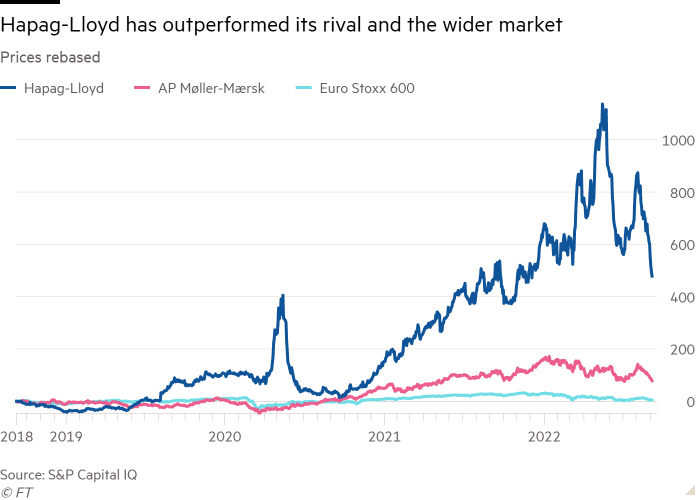

Container shipping groups from Mediterranean Shipping Company and AP Møller Maersk to CMA CGM and Hapag-Lloyd have experienced a “once in a lifetime” market boom.

“Earning the money they have done in the past two years is intoxicating,” said Simon Heaney, a senior manager at Drewry, the shipping research group. Drewry forecasts the industry’s profits for 2021-23 will equal the amount it made between the 1950s, when container ships were first built, and 2020.

“It’s something you see once in a lifetime, maybe not even that,” said Rolf Habben Jansen, chief executive of Hapag-Lloyd, the German carrier that is the industry’s fifth-largest by capacity.

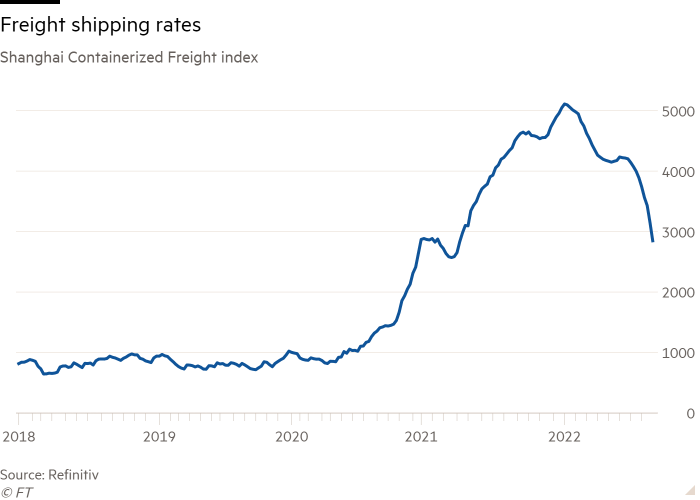

But the container shipping cycle appears to have peaked.

Port congestion worldwide is still high, which has forced up prices and helped profits, with ports such as Felixstowe in the UK hit by strikes. Yet freight rates have fallen by about a third and profitability is set to decline next year, analysts believe.

On top of that, fears abound of both sky-high inflation and possible recessions in many western countries.

So how will an industry used to boom-bust cycles react and cope? Have container shipping companies used the good times well enough to prepare for squallier conditions?

Container shipping companies are the prime agents of globalisation, transporting goods from shoes to food across the oceans, particularly from manufacturers in Asia to consumers in Europe and the US.

After the first wave of Covid-19 in 2020, container shipping groups and consumer goods companies alike were surprised at the sharp rebound in spending, particularly online.

Drewry estimates that the entire industry made an operating profit of just $7bn in 2019, and $26bn in 2020. But in 2021, as companies paid ever higher rates to get the goods they needed, operating profits jumped to $210bn and are forecast to reach $270bn this year.

“I certainly hope we will not see a pandemic of this nature again, certainly in my lifetime. It’s been a dramatic period. We are looking forward to a more normalised world. We believe we have used this period to build a much better business,” said Søren Skou, Maersk’s chief executive.

Carriers have used the bumper profits to repair their balance sheets, many of which were still stricken after the 2008-09 global financial crisis brought an end to high levels of growth.

Heaney said that in 2020 many carriers still had balance sheets that Drewry classified as “red” while now nearly all were “green”, indicating that they were healthy.

Many of the bigger groups, such as the big three of MSC, Maersk, and CMA CGM, have used their soaring profits to move more into logistics, hoping to build a reasonable counterweight to their more volatile shipping businesses.

Maersk has made numerous land-based acquisitions, culminating in December’s $3.6bn purchase of Li & Fung’s contract logistics business in Asia.

Revenues at its logistics business have more than doubled in the past two years, although they remain about a fifth of the level of its container business.

Shareholders have also benefited from the boom, with exceptional dividends and buybacks from some of the listed groups. “Shareholders have helped us through 10 years of crisis, putting money in, and now they get rewarded for that,” said Jansen.

Most crucially, however, the performance of shipping groups in a downturn might be undermined by their use of record earnings to buy more ships.

Vessels normally take two to three years to be delivered, meaning many will arrive in what are expected to be very different economic conditions, a typical curse of the industry.

The capacity of ships on order compared with the current capacity at sea has risen from a low of 8 per cent in 2020 to 28 per cent, according to data specialist Alphaliner.

“I think carriers will regret how they have added capacity this year,” said Heaney. “If a recession comes and demand for containers drops off much quicker than we are anticipating, then it will speed up recovery for ports and the release of capacity. There are lots of new builds arriving. There is a risk of large-scale overcapacity next year.”

Jansen said he “hoped” container shipping companies would be more rational in this downturn than previous ones but conceded he did not know for sure. “This industry has always been cyclical. I don’t think that will change,” he added.

One difference from previous downturns is that the industry is more consolidated, with the biggest players having more scale and being part of networks with other carriers that allow them to tweak capacity jointly.

Jansen said Hapag-Lloyd lost $7mn a day in revenues at the start of the pandemic, concentrating the mind.

“You see the hits you get if something goes wrong are bigger, so it maybe makes you more conservative. The sheer magnitude of these numbers makes us probably act a bit quicker,” he added.

In Copenhagen, Skou is particularly concerned about Europe where consumer confidence is low, war is still raging in Ukraine and imports have fallen back to pre-pandemic levels.

Still, the Maersk chief executive is relatively confident as he expects the chronic supply chain congestion to start to ease at the end of this year.

“I don’t see a hard landing for Maersk. If demand drops a lot, we will have to adjust the capacity . . . I know how we’re going to act in a slowdown situation,” he said. “What matters for global container shipping is not how many ships exist but how much capacity is deployed compared to the demand out there.”

He pointed to more and more customers signing long-term contracts, locking in high freight rates, as well as its push into logistics helping to “substitute” some of the earnings it is likely to lose in shipping.

Carriers also have tools at their disposal to reduce capacity through scrapping or idling vessels, pushing back deliveries of new ships, or cancelling sailings.

Scrapping ships fell to zero in the past few years as carriers pressed all vessels into service, but with new environmental standards coming into force there is likely to be more.

However, there are few certainties, especially in an industry with a tradition of acting irrationally. Heaney said analysts at Drewry were split on whether this time would be different.

“I’m pessimistic that carriers have changed their behaviour completely,” he said, before adding: “They are better equipped than previously. The odds are better than they have been.”

For now, industry and analysts alike are forecasting a gradual normalisation.

Earnings next year are likely to be lower but still well above the pre-pandemic level. Supply chain woes provide a support even as freight rates and volumes fall.

But the danger is that a sudden economic slowdown in the developed world leads to a sharp reversal that unblocks supply chains and ports quicker than expected, which would be bad for profits as the forces that led to sky-high prices could unwind quickly.

Heaney said: “It’s the beginning of the end [of the boom]. But it’s not going to be an overnight thing. There are no guarantees at the moment.”

Comentarios recientes